Entering stories: decoding born-digital fiction writing through keystroke logging

Slide 1

How nice that you all came. Before the committee starts asking me tough questions about my dissertation, I’d like to take this opportunity to tell you a bit about what I’ve been researching over the past few years: how writers work in a digital medium.

Whereas on paper drafts you can find erasures, additions, and maybe even blood sweat and tears, with digital documents it is not a given that you can still find traces of the creative process. Some writers faithfully create dated versions and put them in a nice folder structure; others work in the same file for months and then throw it away.

Most word processors do not have a good system for permanently preserving a document’s history. Therefore, for my research I invited writers to work with special software that does capture all the changes in the document, in the right order and time-stamped.

Twelve writers participated in this research in this way. They spent between 7 and almost 40 hours working on their stories, in the winter of 2020. Some of them are also here today. Gie Bogaert, Roos van Rijswijk, Dirk Speelman, Jens Meijen, Ellen Van Pelt, Renée van Marissing, Niels ’t Hooft, David Troch, Aafke Romeijn, Vincent Merckx, Jente Posthuma and Arnoud Rigter. I am very grateful to them.

Slide 2

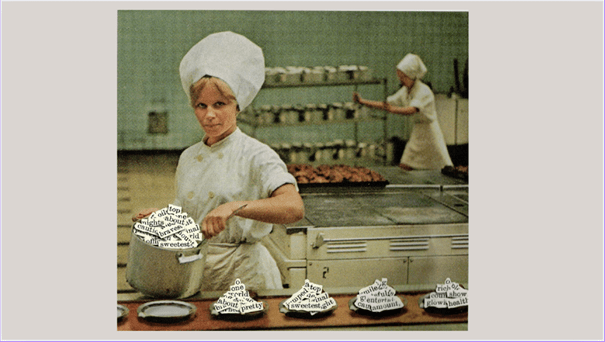

I thought it would be good to just start at the beginning of my book, namely the cover. I felt that this collage art by Toon Joosen fits well with the topic of digital creative writing. Unlike the romance of the fountain pen and the charm of the moleskin notebook, we may see writing on the computer as assembly line work; the environment is the same for almost all writers (Microsoft Word, and otherwise Libre Office, Pages or possibly Scrivener or Google Docs, but those are the rebels.) And you can’t tell the personality and emotional state of the writers from a font, either. And then those lines, just filling up the white from left to right every time – no doodles, no diagonal or circular sentences, no freedom – just like a conveyor belt, in other words.

In this picture, however, we can also see that on each plate there is a completely unique combination of words. In addition, fortunately, there is a hefty ladle to find the right words under considerable stirring, until the story has solidified into its final form. That stirring in sentences is something literary writers also do all the time, and already while typing new material. After all, in a digital working environment you can change your text very easily, there is plenty of room – unlike on a sheet of paper.

It is also striking that this writer looks straight at us, the readers. We know from professional writers that while working they are not only concerned with what they want to express themselves, but also already with how things are going to come across to the reader. For example, I noticed that some of “my” writers made certain explicit information more implicit, to give the reader a chance to participate in creating the story world themselves.

Slide 3

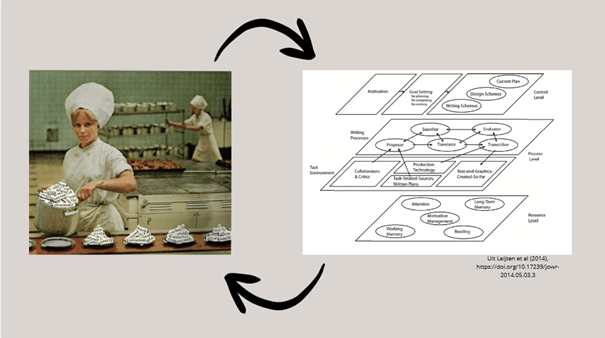

Now let’s try to look into the writer’s head. Here you can see a cognitive model of the writing process. To stay with the cooking metaphor for a moment; you can think of this one as a recipe: it lists a number of ingredients you need to have on hand, as well as a number of steps or activities you need to go through to produce a text. Unlike baking a cake, where the order of steps is fixed, and you only have to perform each step once, we know that in writing these activities have no fixed order, and also that you are likely to go through all the steps more than once. In short, you switch between production and reflection, you might say cooking and tasting. This happens at different levels; if you look at a writing process as a whole, it is most like baking a cake: you might see, for example, that a writer first makes a plan, then writes a first draft, and then does some editing. If you zoom in further, however, you see that these activities constantly alternate.

How and when and on what scale writers switch between those activities, and how much attention they pay to the different activities has been studied mostly for writing very short informational or academic texts, and mostly looking at learning writers, such as children and students. Because creative digital writing processes of professional fiction writers have not yet been looked at in this way, this project is an initial exploration. I provide an inside look at these writers, each time asking; How did the participants use those ingredients and intersperse the activities over time? And how do these writers differ in this?

Slide 4

This model is based on informational and academic writing processes. I found that 1 ingredient was still missing for fiction writing: imagination, or “simulation.

Slide 5

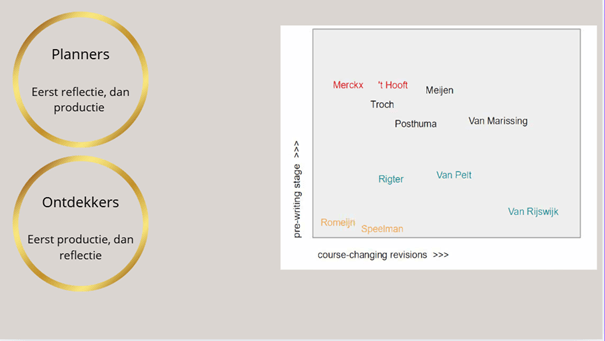

Several theories already existed about what types of fiction writers exist. The most common one divides them into two basic types. Those who prefer to reflect first and then produce: planners, and those who produce first and then reflect and adjust: discoverers.

I show that this division doesn’t work so well for digital writing. It makes more sense to distinguish two dimensions: Revision and Planning in advance. That way you actually get four prototypes. And when I use these to interpret my participants’ processes you get this artistic representation. For example, Roos van Rijswijk did not make a plan in advance, and incorporated many new ideas into her text while writing. And Renée van Marissing had both extensive preparation with plans and notes, and a considerable change of direction during the writing.

Slide 6

I also tried to make that difference between production and reflection quantitative by developing a new method, together with my supervisor Luuk van Waes and with Rianne Conijn. Besides looking at the text versions themselves, I looked at the movements of the cursor. When someone produces mostly new text, that cursor moves one step to the right each time. If the cursor jumps to elsewhere in the document, to change something about the text there, the production “flow” has been broken by reflection.

On this graph, each writing session is a shape. The blue spheres are sessions in which production was more central, and the orange and red shapes represent sessions in which the writers ‘jumped’ more and longer through their document. I found that three types emerged from it; writers who immediately engaged in a lot of revision in all sorts of places in the text, so a lot of red and orange, like Jente Posthuma. Then there are writers who first focus on expanding the text, i.e. mainly production, and later become more reflective. An example is David Troch’s process. There were also writers who in some sessions were a bit more in the production flow and in others were doing more revisions on older parts of the text, such as Vincent Merckx. And then there was Aafke Romeijn, who did a fantastic job demonstrating that you can also use a computer as a typewriter.

Slide 7

Cursor jumps may not be the most imaginative part of a creative writing process. I was pretty much done with it myself at one point, and then interpreted all revisions of three of the processes. This was made easier because my colleague Lamyk Bekius had created an online edition where you can see all the text changes in context. This site is now open to everyone by the way, so you can take a look for yourself.

In this image you can see that Ellen Van Pelt changed a lot about the style of her story, and less about the plot, setting or characters (that fell under the category of meaning-changing). You can also see that over the course of the process, she shifted her focus somewhat from meaning-changing revisions to stylistic revisions.

Slide 8

Hopefully I have been able to make clear to you what I have enjoyed working on over the past few years. Occasionally I get asked why my research, and indeed this type of research in general, matters. Well, I don’t think there are any haters in the room, but I want to close with a short answer to this in the words of writer and poet Ben Okri: “Stories are the highest technology of being. There is in story the greatest psychology of existence, of living.” (from The Mystery Feast, Thoughts on Storytelling, Clairview Books, 2015). Stories matter, and stepping into those stories to see how they come about has led to a new story, in the form of my dissertation. Thank you.